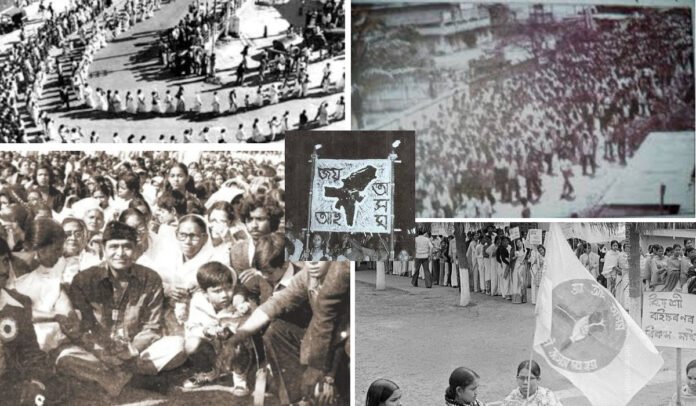

I grew up amidst the chants of protest and the acrid sting of tear gas drifting through the streets of Assam. As a child in the late 1970s and early 1980s, I watched my mother, my uncles and aunts, and even our neighbours leave behind the safety of their homes to march in the Assam Agitation. It was not some distant political movement; it was a visceral struggle that consumed the very rhythm of daily life. Schooling was interrupted, careers were abandoned, and lives were extinguished in the name of safeguarding our homeland. More than eight hundred and fifty martyrs gave their lives, believing that their sacrifice would secure the identity and dignity of future generations. Yet today, I cannot help but ask—for what?

The Government of India’s recent order under the Immigration and Foreigners Act, 2025 has reopened old wounds. By permitting non-Muslim migrants from Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan who entered India on or before 31 December 2024 to remain even without valid documents, Delhi has once again shifted the goalposts. For policymakers, this may appear a gesture of humanitarian relief. But for us in Assam, it feels like the slow unravelling of the Assam Accord of 1985, the very pact that was supposed to guarantee our survival.

The blow first fell with the Citizenship (Amendment) Act, 2019, which had already extended the cut-off date for such migrants to 31 December 2014. That Act effectively nullified the Accord’s solemn deadline of 24 March 1971, a date consecrated by blood and compromise. It was not simply a legal threshold; it was the cornerstone of trust between the Assamese people and the Indian state.

Now, with the 2025 order, the cut-off has been pushed yet another decade forward. Each such extension is more than an administrative adjustment; it is a symbolic betrayal. It tells every family who lost a loved one in the agitation that their sacrifice has been treated as expendable. It reopens scars that had never truly healed.

For the rest of India, this is an abstract debate about refugee protection. For us, it is an existential crisis. The demographic equilibrium of Assam is already precarious. The Assamese language, culture and political voice stand imperilled. In village after village, town after town, quiet demographic shifts erode the very essence of our homeland. The threat is not merely economic or electoral; it is civilisational.

I am not without compassion for those fleeing persecution. Yet I ask: why must Assam perpetually bear the disproportionate burden of India’s refugee policies? Why must our fragile identity be sacrificed at the altar of national humanitarianism?

When I recall the faces of my family and neighbours, chanting through the streets in those turbulent years, I struggle to find words. They believed their courage would protect us, that the Accord enshrined their sacrifice. Today, as Delhi moves the goalposts yet again, I am left with the most painful of questions: was it all for nothing?